Pacific Walrus

The Pacific walrus is a subspecies of walrus (Odobenus rosmarus) found in the Bering, Chukchi, Laptev and East Siberian Seas. The reliance of walruses on sea ice for resting during the summer foraging period makes them vulnerable to changes in climate and the associated loss of sea ice.

All walruses have tusks, but tusks tend to be longer and thicker in males than females.

Species Status

Abundance and Trends

The first documented aerial survey of Pacific walruses was conducted jointly by the United States and the former Soviet Union in 1975, after the enactment of the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) in 1972. This survey provided an estimate of about 246,000 animals and subsequent surveys suggested a population decrease to about 201,000 by 1990. The most recent aerial survey, conducted in 2006 by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), estimated the walrus population to be about 129,000 but with a large confidence interval of 55,000-550,000 animals. The 2006 survey did not cover the entire walrus range and therefore is likely to be an underestimate of the total population size.

Although the estimates between 1975 and 2006 suggest that the population declined, the differences in methods and geographic coverage between the surveys make it impossible to determine population trends over time. Surveying walruses is difficult because during the spring, when the surveys are conducted, walruses are distributed widely across the Bering Sea pack ice and spend a significant portion of their time in the water. Adverse weather conditions in this region further hinder survey efforts.

Faced with these difficulties, FWS began testing new population estimation methods in 2012 using a mark-recapture approach. The final study, published in 2022, analyzed data from 2013 to 2017 and estimated Pacific walrus abundance to be approximately 257,000 animals. Beginning in 2023, FWS, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), and Alaska Native hunters partnered to conduct annual vessel-based research expeditions to reassess age structure and abundance of Pacific walruses. While that work is ongoing, USGS has also used satellite imagery from 2017 to 2023 to estimate a minimum population size of 250,000 walruses.

Pacific walrus abundance is expected to decline as sea ice loss continues, although the magnitude of the predicted decline is unknown. Overall, walrus population growth rates tend to be slow, with mature females producing a calf on average every 3 years. However, natural mortality also tends to be low and walruses can be long-lived. Their only natural predators include polar bears and killer whales. They are also harvested for subsistence purposes by Alaska Natives, as authorized under the MMPA.

Distribution

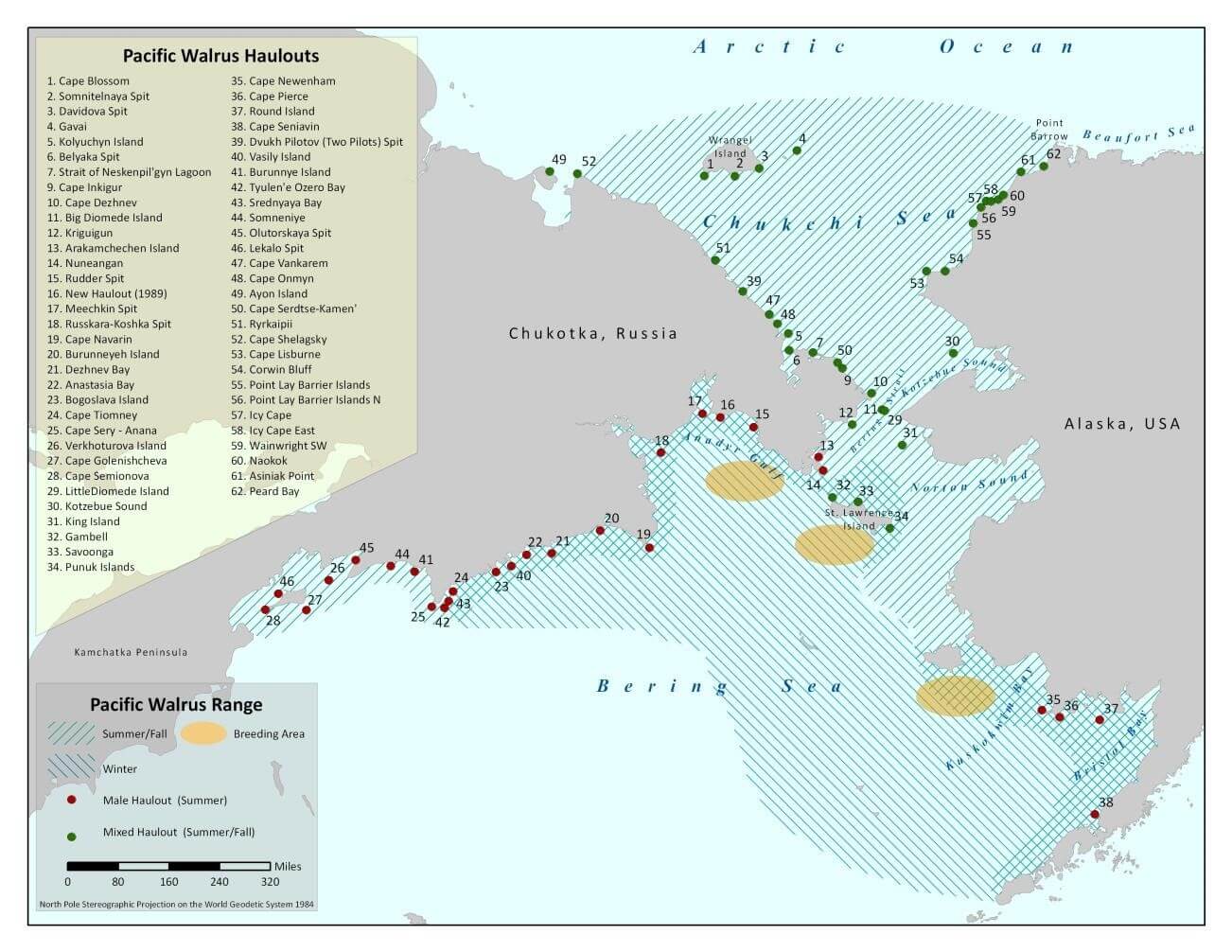

Pacific walruses range across the continental shelf waters of the northern Bering Sea and Chukchi Sea. Because they rely on broken ice habitat and coastal haulouts to access feeding areas on the ocean floor, their distribution varies in response to seasonal and annual changes in sea ice cover. In the winter, breeding aggregations form in the Bering Sea pack ice where there is access to open water. As the sea ice retreats in the spring, most walruses migrate north to feeding areas in the Chukchi Sea. In years with low sea ice, walruses may migrate into the Beaufort and East Siberian Seas. Those walruses are often associated with loose pack ice, but will use coastal haulouts once the sea ice retreats north of the continental shelf waters. Most adult male walruses, as well as some adult females and juveniles, remain in the Bering Sea and use coastal haulouts throughout the summer feeding season. As sea ice begins to form again in the fall, walruses that migrated north for the summer typically return south.

Seasonal distribution, breeding areas, and coastal haulouts of Pacific walruses. (Smith 2010; FWS 2011)

Pacific Walruses and Climate Change

Walruses rest on sea ice when it is available, but will use coastal haulouts when sea ice is not present. Since 2007, summer sea ice in the Chukchi Sea has retreated offshore to areas too deep for walruses to reach the ocean floor to feed. As a result, many walruses have to travel farther to reach their foraging grounds and are now using coastal haulouts to rest between foraging trips. Thousands of walruses have been observed on land in the U.S. and Russia during late summer. Some of the coastal haulouts are located near communities where human activity and the presence of predators, like polar bears, may disturb walruses. When large groups of walruses are disturbed, subsequent stampedes can cause the trampling and death of many walruses. Stampedes not only result in trampled young animals, but can separate mothers and calves and cause injury and death of weak animals recovering from prolonged foraging trips. Additionally, traveling farther to reach foraging grounds will increase walrus energetic demands. These and other impacts of climate change and anthropogenic disturbance are likely to result in reduced overall abundance and population growth rate of walrus under a range of potential future conditions. Reduced carbon emissions and efforts to protect important haulouts and foraging grounds may help mitigate those effects.

To gain a better understanding of walrus distribution, abundance, and the formation of large coastal haulouts in response to climate change, USGS has developed methods to monitor walruses using satellite imagery. Satellite imagery allows scientists to easily monitor extremely remote locations, and recent methods using synthetic aperture radar, which relies on radar signals bouncing off Earth’s surface, can capture images of haulouts regardless of weather or time of day. Satellite imagery is being used to monitor shifts in the use of coastal haulouts and to estimate the minimum population size of Pacific walruses.

What the Commission Is Doing

The Marine Mammal Commission maintains close contact with Alaska Native communities that rely on walruses as a source of subsistence. In February 2016, the Commission led a series of listening sessions in Alaska to learn more about the challenges that Alaska Natives are facing as a result of climate change. Participants in those sessions noted that walruses are becoming more difficult to access due to adverse ice and weather conditions.

Commission Reports and Publications

For more information on the Pacific walrus, see the Commission’s 2010-2011 Annual report (pages 178-182) and 2012 Annual Report (pages 55-59).

Commission Letters

| Letter Date | Letter Description |

|---|---|

| May 8, 2023 | |

| June 30, 2021 | |

| November 10, 2020 | Notice of plans to conduct Alaskan Arctic Coast Port Access Route Study |

| June 13, 2017 | |

| July 7, 2016 | |

| October 30, 2015 | |

| July 17, 2013 | Draft stock assessment reports for Pacific walrus and three stocks of Northern sea otters in Alaska |

| February 8, 2013 | |

| June 20, 2012 | Listing of the polar bear, walrus, and narwhal on CITES Appendices |

| January 3, 2011 | Listing the Pacific walrus as threatened under the Endangered Species Act |

Learn More

Threats

The greatest threat to the Pacific walrus is climate change. As the pack ice that they rely on during the summer foraging season in the Chukchi Sea diminishes, walruses are increasingly forced to seek refuge at land-based haul out sites. Over the last two decades, large aggregations of animals have been observed at haulout sites near Point Lay, Alaska. Such aggregations may be dangerous for calves and juveniles if disturbance by humans or other factors cause adults to stampede. Local communities have taken important measures, in collaboration with FWS, to limit the potential for such disturbance.

Reduction of sea ice and ocean warming are also expected to increase the frequency, intensity, and geographic range of harmful algal blooms (HABs) in the Arctic. Two of the most common HAB toxins on the west coast of North America are domoic acid and saxitoxin. Those toxins, associated with amnesic and paralytic shellfish poisoning in humans, can also cause illness and death in marine mammals. A 2016 study reported that out of 13 Alaskan marine mammal species, Pacific walruses contained the highest concentrations of both domoic acid and saxitoxin. No abnormal behaviors of the sampled walruses were reported, so it is unlikely that toxicological effects have occurred; however, toxin concentrations were in the range known to cause illness and/or death in California sea lions, humpback whales, and humans, and two walruses sampled in 2019 had saxitoxin concentrations near the seafood safety regulatory limit. There is concern that increased exposure to biotoxins as sea ice continues to melt may increase the risk to both marine mammals and the people that rely on them for subsistence.

Disturbance from a variety of human activities in the Arctic, such as shipping and oil and gas development, can also have negative impacts on walruses. Marine traffic and noise associated with seismic surveys could interfere with the walrus migration or cause changes in behavior in the foraging grounds.

Although hunting of walruses for subsistence use could be considered a threat to the walrus population, current harvest levels are thought to be sustainable and will continue to be as long as harvest is adapted to match changes in population dynamics.

Current Conservation Efforts

In 2008, FWS was petitioned to list the walrus as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and to designate critical habitat for the species. After a review of the best available science in 2011, FWS found that listing the walrus as threatened or endangered was warranted. However, the walrus remained a candidate species as FWS first considered other higher-priority species for listing. FWS made a final decision on the listing of Pacific walrus in October 2017 with the determination that the species does not warrant listing as threatened or endangered under the ESA. The Center for Biological Diversity (CBD) subsequently sued FWS in 2018 for not listing the walrus under the ESA, which was then rejected by a federal judge. After an appeal from CBD, the appeals court ruled in June 2021 that FWS had not provided sufficient justification for reversing its 2011 listing decision and must still do so. Walruses currently are afforded protection in the United States (with the exception of subsistence harvest by Alaska Natives) under the MMPA and they are listed in Appendix III of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).

In 2020, the U.S. Coast Guard requested input on routing measures to minimize the impact of increased shipping on marine mammals, Alaska Native communities, and the marine ecosystem. The Commission analyzed the distribution and seasonal movements of numerous marine mammal species, including Pacific walrus, and submitted a letter to the U.S. Coast Guard recommending preferred and alternative shipping routes to protect marine mammals. Recommended areas to be avoided to minimize disturbance to walruses included areas where they aggregate in large groups to feed and rest, such as Hanna Shoal and Point Lay. The public comment period for this Port Access Route Study closed in September 2021.

Additional Resources

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – Marine Mammal Management – Alaska Region – Walrus

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – 2017 Final ESA Listing Decision for Pacific Walrus

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – Revised 2023 Pacific Walrus Stock Assessment Report – Alaska Stock

Pacific Walrus Coastal Haulout Database 1852-2016

U.S. Geological Survey – Alaska Science Center – Walrus Research

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) – Walrus