Oil and Gas Development and Marine Mammals

The first drilling for oil in ocean waters took place in 1896, off the coast of California. Since then, offshore drilling has pushed the limits of technology and innovation, with the deepest wells now being drilled in waters more than 1,500 meters deep. Oil and gas represents a significant source of energy as well as revenues, but the development of oil and gas resources can pose considerable impacts on marine mammals and marine environments.

What the Commission Is Doing

The Commission regularly reviews and comments on Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) proposed oil and gas activities and on proposed Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) incidental take authorizations in all U.S. federal waters, also referred to as the U.S. Outer Continental Shelf (OCS). We also comment on and promote environmental studies to better understand the potential effects of oil and gas activities on marine mammals, and facilitate efforts to identify, prioritize, and address information needs through the convening of workshops and meetings.

Commission comments related to federal oil and gas activities on the U.S. OCS are listed below; all Commission comments are available on the Commission’s letters webpage. Commission-sponsored projects and workshops related to offshore energy development and oil spill response are available on the Commission’s workshop reports webpage.

Regulatory Framework for Oil and Gas Leasing

After the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of America (formerly the Gulf of Mexico), the Department of the Interior (DOI) re-structured responsibilities within the department for the regulation, enforcement, and revenue collections associated with offshore oil and gas development:

- Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM): charged with balanced and responsible development of conventional and renewable energy resources in the U.S. OCS, including resource evaluation, planning, and other activities related to leasing;

- Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE): charged with comprehensive oversight, safety, and environmental protection related to offshore energy activities; and

- Office of Natural Resources Revenue (ONRR): charged with royalty and revenue management for offshore energy leasing and development, including the collection and distribution of revenue, auditing and compliance, and asset management.

The Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act (OCSLA) provides the statutory and regulatory framework for oil and gas development on the U.S. OCS. The Act outlines a four-stage process for oil and gas development.

Oil and Gas Activities, 2017 to Present

Oil and Gas Five-Year Leasing Programs

Section 18 of OCSLA authorizes the Secretary of the Interior, through BOEM, to establish a schedule for oil and gas lease sales for a period of five years, with a mandate to consider environmental and socioeconomic requirements as well as other factors outlined in the law. The development of the 2017-2022 leasing program was initiated by BOEM in June 2014. The Draft Proposed Program was issued in January 2015 followed by the Proposed Program in March 2016 and the Proposed Final Program in November 2016. The leasing schedule included eleven lease sales in four OCS planning areas, including one sale in Cook Inlet and ten area-wide lease sales in the Gulf of America region. Eight of the ten scheduled lease sales in the Gulf were held according to the schedule in the leasing program, but the remaining two lease sales in the Gulf, as well as a scheduled lease sale in Cook Inlet, Alaska, were cancelled by the Biden Administration in May 2022. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 reinstated the three cancelled lease sales and put forward a schedule for them to be conducted by the end of 2023.

The current five-year leasing program covers the 2024-2029 time period. The Proposed Final Oil & Gas Leasing Program for 2024-2029 was announced by BOEM on September 29, 2023, and approved by the Secretary of the Interior on December 1, 2023. The 2024-2029 leasing program includes three lease sales in the Gulf of America, scheduled for 2025, 2027, and 2029. The program represented a narrowing of lease sales from the eleven potential lease sales evaluated by BOEM in its Proposed Oil & Gas Leasing Program for 2023-2028 (ten in the Gulf and one in Cook Inlet), and the 47 lease sales evaluated by BOEM in its Draft Proposed Oil & Gas Leasing Program for 2019-2024. The timing of the three lease sales in the 2024-2029 leasing program allows the Administration to meet the requirements of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 to hold oil and gas lease sales in the year prior to holding additional lease sales for offshore wind energy development.

Presidential Actions Affecting Oil and Gas Leasing Areas

President Barack Obama issued several directives related to oil and gas leasing in offshore waters of the United States. In March 2010, the President withdrew Bristol Bay from leasing through 30 June 2017. In December 2014, the President withdrew the entire North Aleutian Basin planning area, which includes Bristol Bay, from all future leasing. In January 2015, the President withdrew certain areas within the Beaufort and Chukchi Sea planning areas in the Arctic from future leasing, including Hanna Shoal within the Chukchi Sea. In December 2016, the President withdrew from oil and gas leasing the Chukchi Sea Planning Area and certain portions of the Beaufort Sea Planning Area, as well as portions of the Bering Sea (the Norton Basin and lease blocks within the St. Matthew-Hall Planning Area lying with 25 nautical miles of St. Lawrence Island). At the same time, the President withdrew from future leasing certain offshore canyon areas of the Atlantic OCS.

On 28 April 2017, President Donald Trump issued Executive Order 13795: Implementing an America-First Offshore Energy Strategy. It encouraged energy exploration and production on the OCS to “maintain the Nation’s position as a global energy leader and foster energy security and resilience for the benefit of the American people, while ensuring that any such activity is safe and environmentally responsible.” As such, the Executive Order directed the Secretary of the Interior to consider revising the schedule of proposed oil and gas lease sales for 2017-2022, including, but not limited to, annual lease sales in the Western and Central Gulf of America, Chukchi Sea, Beaufort Sea, Cook Inlet, Mid-Atlantic, and South Atlantic OCS planning areas, stipulating that any revisions made not hinder or affect ongoing lease sales.

[In response to Executive Order 13795, the Commission submitted comments to BOEM on the development of a new five-year National OCS oil and gas leasing program for 2019-2024, and to NOAA on both the Marine Mammal Acoustic Technical Guidance and the review of National Marine Sanctuaries and Marine National Monuments (see letters section below).]

On 8 September 2020, President Trump signed a Presidential Memorandum that withdrew from leasing consideration, for 10 years (starting on 1 July 2022 and ending 30 June 2032), portions of the eastern and central Gulf currently excluded from leasing under section 104(a) of the Gulf of Mexico Energy Security Act of 2006. The memorandum also excluded from leasing, for the same time period, the South Atlantic and Straits of Florida OCS planning areas. [The memorandum applied to renewable energy as well as oil and gas leasing; however, the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 authorized the Biden Administration to resume wind energy leasing in those previously withdrawn areas.]

Upon entering office on 20 January 2021, President Joseph Biden signed Executive Order 13990 restoring the withdrawal of certain offshore areas in Arctic waters and the Bering Sea from oil and gas leasing. The President also called for a temporary moratorium on all Federal activities related to the implementation of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge Coastal Plain oil and gas leasing program. On 27 January 2021, President Biden signed Executive Order 14008, which called for a pause in oil and gas leases on federal lands and offshore waters pending completion of a comprehensive review and reconsideration of federal oil and gas permitting and leasing practices. That Executive Order resulted in BOEM’s subsequent announcement to cancel actions being taken to hold lease sale 258 in federal waters of Cook Inlet, Alaska. BOEM also rescinded its Record of Decision for lease sale 257 in the Gulf , which effectively cancelled the lease sale that was scheduled to take place in March 2021. The pause on oil and gas leasing was lifted by the DOI in August 2021, allowing Lease Sales 257 to go forward while it continued its required review. That review was completed in November 2021, and identified significant shortcomings in the federal oil and gas leasing program, including (1) providing a fair return to American taxpayers and states, (2) designing more responsible leasing processes, and (3) creating a more inclusive and just approach to managing public lands and waters. DOI’s report outlined actions it would take to address the identified shortcomings. The report also encouraged Congress to enact legislation that would provide fundamental reforms to onshore and offshore oil and gas programs. On May 11, 2022, the Biden administration announced that it was cancelling all remaining lease sales in the 2017-2022 leasing program, including one in Cook Inlet, Alaska, and two in the Gulf of America. [As noted above, the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 reinstated the three cancelled lease sales, directing them to be held by the end of 2023.]

Programmatic Review of Geological and Geophysical Surveys in the Gulf

In June 2018, NMFS issued a proposed rule for marine mammal take authorizations related to oil and gas-related geophysical surveys in the Gulf. The proposed rule dealt primarily with seismic surveys used in oil and gas exploration and development, but also included consideration of high-resolution geophysical surveys. The final rule was published by NMFS in January 2021, informed by BOEM’s final programmatic environmental impact statement (FEIS) on geological and geophysical activities in Gulf waters. The final rule allows for the issuance of Letters of Authorization (LOAs) to industry operators for the taking of marine mammals incidental to geophysical surveys, in accordance with prescribed, mitigation, monitoring, and reporting requirements. The final rule is effective from April 2021 to April 2026, and NMFS has since issued LOAs to several geophysical survey companies. In April 2024, NMFS revised the rule governing takes of marine mammal incidental to geophysical surveys in the Gulf to correct errors in the calculation of incidental takes of marine mammals and to incorporate new information.

Stages of Oil and Gas Development and Potential Effects on Marine Mammals

Oil and gas development in the marine environment proceeds in stages, all of which have the potential to impact marine mammals. For a quick overview, see stages of oil and gas development and potential effects of concern for marine mammals.

Exploration

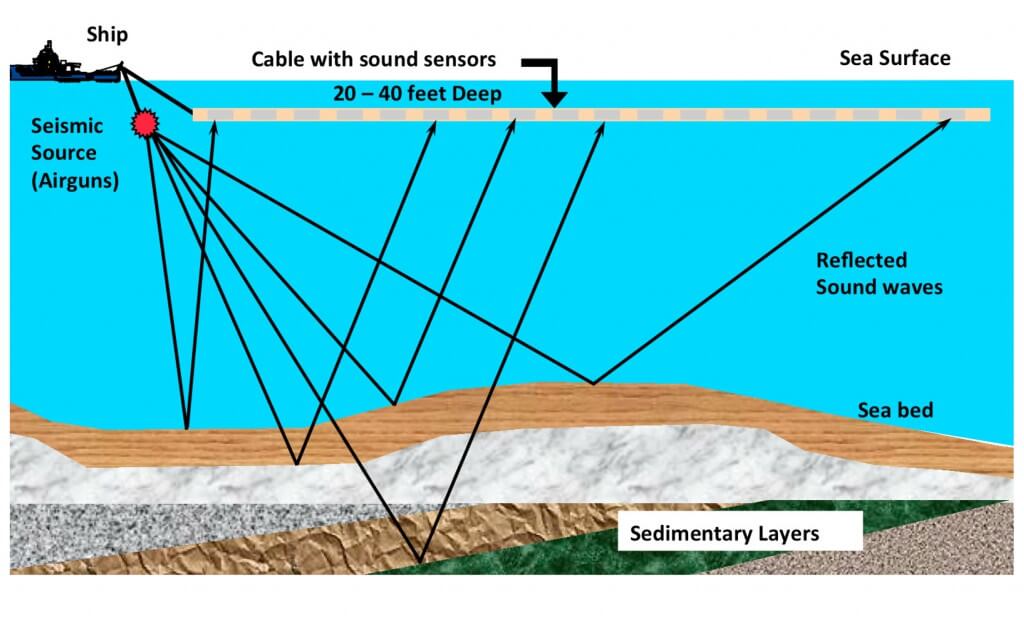

Schematic of offshore seismic survey. (American Petroleum Institute)

Exploration for oil and gas is the process of searching for and characterizing hydrocarbon reserves. The exploration stage involves such geological and geophysical surveys (including seismic surveys, high-resolution geophysical surveys, and gravity and magnetic surveys), sediment sampling, and exploratory drilling. Seismic surveys use a controlled sound source, such as an airgun, to transmit sound waves to the ocean floor. The pattern of reflected waves reveal subsurface features that can indicate the presence of hydrocarbons. Seismic surveys can vary in sound intensity and in the amount of geographic area covered. In general, 2-D seismic surveys are used to collect seismic data over a broad area, 3-D surveys are used to collect a larger set of measurements over a smaller area, and 4-D (or time lapse) surveys are used to collect dense measurements in the same small area repeatedly over time. Wide-azimuth seismic surveys collect geophysical data from many different angles, and are used primarily in the Gulf to investigate oil trapped below salt domes and other subsurface structures.

North Atlantic right whale off the coast of Florida. Photo taken under NOAA research permit #775-1875. (Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission)

Seismic airguns emit high energy, low-frequency impulsive sound that travels long distances. Marine mammal response to seismic surveys can cause disruption of important marine mammal behaviors, and—at close range—physiological injury. Sound from airguns can also mask biologically important sounds, including communication calls between individuals of the same species. Baleen whales (e.g., North Atlantic right whales) are believed to be affected by seismic survey activity because of their sensitivity to low-frequency sounds. However, other cetaceans may also be affected, notably harbor porpoises and beaked whales.

Once seismic surveys are completed, exploratory drilling is used to confirm the presence of hydrocarbon reserves and to make decisions regarding the economic feasibility of developing an oil and gas field. Exploratory drilling in offshore waters generally involves a single well and can occur over weeks, months, or even years, depending on the depth of the well and other geophysical features, weather, availability of equipment or personnel, safety concerns, or other issues. After exploratory drilling has ceased, wells are capped and abandoned either temporarily or permanently.

Exploratory drilling may impact marine mammals based on disturbance by sound emitted during drilling, during seismic profiling of the well, and from support vessels or aircraft. Drilling can also result in oil spills, which can affect marine mammals directly by contact, inhalation, or ingestion, or indirectly by affecting marine mammal prey or habitat. For a more thorough discussion of the potential effects of an oil spill on marine mammals, see our Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill page.

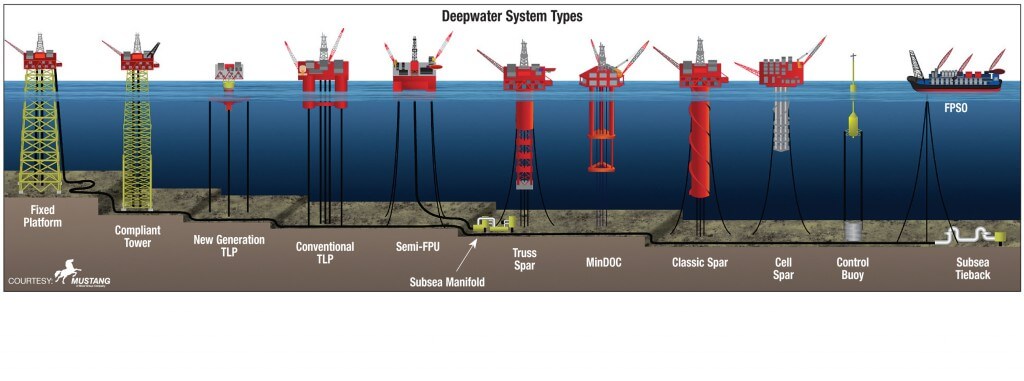

Types of deepwater oil drilling rigs. (Used with permission from 2011 Deepwater Solutions for Concept Selection poster, Wood Group Mustang and Offshore Magazine)

Construction and Installation

If suitable oil and gas reserves are found, the next stage of development involves construction and installation of drilling platforms or structures and transport systems (e.g., pipelines). Construction begins with site surveys and planning, which can involve high-resolution geophysical surveys and result in sound-related effects. Impact pile driving during construction of shallow-water platforms also can be a significant source of low-frequency sound. Both shallow- and deep-water construction can require aircraft and vessel activity, which can cause marine mammals to avoid or move away from preferred habitat and increase the risk of ship strikes. The construction and anchoring of infrastructure and equipment can alter or degrade bottom habitat, which can affect the distribution of marine mammal prey. If oil or gas is to be transported by pipeline, either buried or on the seafloor, more construction activity is required and therefore more sound would be emitted and seabed disturbance can result. Finally, all of these activities may increase the amount of debris in surrounding waters and thus increase ingestion hazards for marine mammals.

Production and Transport

The production stage involves the drilling of one or more wells, extraction of oil and gas, and transport of the oil to refineries and the gas to markets, either through pipelines or in tankers. Depending on the size of the reservoir and the recovery rate, an oil and gas platform may be productive for several decades or longer. Seismic surveys may be conducted on a regular basis to guide drilling activities and monitor changes within the reservoir and the pipeline. Both drilling and seismic activities generate sound that may be harmful to marine mammals. Vessel and aircraft activity is a source of chronic disturbance and vessel activity can increase the potential for ship strikes and fuel spills. Drilling produces muds and cuttings that may be discharged near the well site, injected back into the ground, or collected and disposed of off-site. Certain types of muds and cuttings can introduce heavy metals and other toxic materials into the marine ecosystem. If produced oil is to be transported by vessel, mooring systems may be required with associated anchoring and potential disturbance of seafloor habitat.

Decommissioning and Site Clearance

When economic conditions and conditions within the well reservoir indicate that oil and gas production is no longer warranted, well production is discontinued and the platform and associated infrastructure are decommissioned. This stage of development can result in disturbance of sediment and the discharge of metals associated with the severance, removal, toppling, and/or destruction of platforms, wellheads, cables, and other equipment and structures. Decommissioning can involve various types of non-explosive cutter tools, but a variety of explosives can also be used to remove underwater structures. Both non-explosive and explosive methods can introduce significant sound into the marine environment, which may be harmful to marine mammals and their prey. Abandoned wells also have the potential to leak oil and gas. Under certain circumstances, platforms (or portions of them) may be left in place, where they serve as artificial reefs.

Hydrocarbon and Other Chemical Spills and Leaks

Spills and leaks can occur at all stages of oil and gas development, with varying effects based on the type and amount of substance spilled. Large spills (defined as > 1,000 barrels) can occur from blowouts, other losses of well control, or accidents during loading, transport, and unloading of oil or gas from platforms to shore via vessels or pipelines. Smaller spills and leaks of oil, gas, or other chemicals also can occur from storage tank accidents, transfer mishaps, leaks from fuel tanks, or incidents involving temporarily or permanently abandoned wells. Spills and leaks can cause acute injury or mortality, can have longer-term, sublethal effects on marine mammals, and can degrade habitat.

The Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) is responsible for the promotion of safety and protection of the environment through regulatory oversight and enforcement of regulations governing the oil and gas industry. In 2016, BSEE proposed significant new regulatory safeguards for well control and blowout preventer systems to prevent oil spills based on lessons learned from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. BSEE also issued new drilling rules for the Arctic. BSEE revised and weakened the regulations for well control and blowout preventer systems in May 2019 in an effort to reduce unnecessary burdens on oil and gas companies. BSEE also proposed revisions to weaken the Arctic drilling rule in 2020, but withdrew the proposed revisions in June 2021.

Response efforts to contain and clean up oil spills also have the potential to affect marine mammals through increased sound from vessel traffic as well as increased risk of ship strikes. During the Deepwater Horizon oil spill chemical dispersants were used both at the surface and at depth to disperse oil. Although research on the effects of dispersants increased after the spill, information about those effects on marine mammals is lacking. The use of booms and skimmers to contain and collect surface oil and the burning of oil on the water surface are activities that also have the potential to disturb marine mammals. Burning reduces the overall amount of oil in the marine environment. However, burning also leaves behind a residue of uncertain composition and toxicity, puts additional chemicals into the air, and can kill animals such as sea turtles that get caught in the fires. An investigation into the state of the science regarding the use of dispersants in Arctic waters was conducted by the University of New Hampshire’s Coastal Response Research Center and Center for Spills and Environmental Hazards, with a series of reports published on topics covering efficacy and effectiveness, physical transport and chemical behavior, degradation and fate, eco-toxicity and sub-lethal impacts, and public health and food safety.

Mitigation, Monitoring, and Reporting Requirements for Oil and Gas Activities

Sections 101(a)(5)(A) and (D) of the MMPA provide a mechanism for NMFS and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) to authorize the incidental, but not intentional, taking of small numbers of marine mammals by oil and gas companies or seismic operators. Takes may be authorized provided they would be (1) small in number, (2) have no more than a negligible impact on marine mammals, and (3) have no unmitigable adverse impact on the availability of marine mammals for subsistence uses by Indians, Aleuts, or Eskimos who reside in Alaska (Alaska Natives). Take authorizations for oil and gas activities typically include a suite of mitigation, monitoring, and reporting measures with which operators must comply to prevent or reduce the adverse impacts of oil and gas development on marine mammals.

Many cetaceans may be affected by seismic oil and gas exploration including humpback whales, killer whales, sperm whales, and short-finned pilot whales, which use low frequency sounds in their daily lives. (NOAA)

Mitigation measures for seismic or other sound-generating activities may include ensuring the area is clear of marine mammals prior to the start of operations, gradually increasing the intensity of the sound source to alert marine mammals that may be in the area so that they can move away, shutting down the sound source if marine mammals approach close enough to be injured, and prohibiting operations at night or during low-visibility conditions. To minimize the probability of vessel strikes, vessels may be required to slow down within a certain distance of marine mammals. Aircraft operating in an area may be required to fly above a certain altitude to avoid disturbing marine mammals. Proposed activities also may be prohibited in sensitive areas at specific times (such as during calving, breeding, feeding, or resting, or during subsistence hunting in Alaska). General and site-specific mitigation measures are based, to the extent possible, on observations of animals exposed to various industrial activities and the animal’s hearing abilities and behavioral response. Nevertheless, the effectiveness of many mitigation measures has yet to be determined.

Alternatives to seismic airguns include the use of marine vibroseis (which is typically used on shore), deep-towed acoustics/geophysics systems, low-frequency passive acoustic systems, and controlled source electromagnetic systems. Some have the potential to replace seismic airguns for offshore surveys, but all are still in various stages of development or testing and not yet commercially available. Modeling to compare the effects on marine mammals from sounds produced by marine vibroseis and seismic air guns predicted that, in general, fewer marine mammals would be affected by marine vibroseis than air gun arrays.

Monitoring for the presence of marine mammals in areas around and potentially affected by oil and gas activities serves two main functions. First, monitoring is necessary to implement mitigation measures, such as a shut-down of the sound source. Second, monitoring should document the effects of an activity, including the number of marine mammals taken and the type of taking. Such information is useful for evaluating the effectiveness of mitigation measures and refining or developing such measures for future activities.

Marine mammal sightings must be documented and reported to the agency that issued the incidental take authorization, both during an activity and at its completion. Immediate reporting of a dead or seriously injured marine mammal is also required, with immediate suspension of operations generally required if the death or injury might have been caused by that activity.

Learn more about the history of oil and gas development in the U.S. OCS.