Marine Mammal Health and Strandings

Connections among Marine Mammal Health, Ocean Health, and Human Health

HPAI and Marine Mammals

An ongoing global epizootic caused by a highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (HPAI) is posing serious threats for marine mammals. It has caused massive die-offs of seals and sea lions in South America, smaller epidemics in seals in North America and Europe, and sporadic deaths of dolphins in North America, Europe and South America. Read more from the Commission’s HPAI factsheet, and find a map of the latest detections in mammals in the US on the USDA website.

The health of our oceans, marine mammal, and people are inextricably linked. Similar to humans, marine mammals are long-lived, and often swim in the same coastal waters and eat the same fish or shellfish as people. Like humans, they breathe air, making them vulnerable to aerosolized harmful algal bloom (HAB) toxins and infectious respiratory pathogens. They often feed high in the food web, making them susceptible to ingestion of HAB toxins and the persistent chemical pollutants that magnify through the marine food chain. Increases in reports of diseases in marine mammals have raised concerns that ocean health is deteriorating (Simeone et al. 2015).

Understanding Marine Mammal Health

Investigating Marine Mammal Strandings

Marine mammals are adapted for a life in the ocean, but may strand on shore due to environmental conditions, disease or following death at sea. Investigations of these stranding events increase our understanding of the health of marine mammals and, by their connection to it, the health of the ocean. Understanding these factors is crucial to meeting the Marine Mammal Commission’s primary goal to maintain marine mammals as functioning elements of healthy ecosystems.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response Program (MMHSRP) was established under Title IV of the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) and is responsible for coordinating national response to stranded pinnipeds (seals) and cetaceans (whales). The MMHSRP does this through collaborations with federal and state facilities as well as via a volunteer network of regional stranding responders, involving aquaria, academic institutions, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). For more information about reporting a stranded, beached, or injured marine mammal, visit NOAA’s stranding page for hotline information.

Marine Mammal Commissioner and veterinarian, Dr. Frances Gulland, responds to a stranded whale. (The Marine Mammal Center)

The activities and capacities of stranding network member institutions may be supplemented or enhanced through an annual program of competitive federal Prescott grants. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) coordinates responses to stranded manatees, sea otters, polar bears, and walruses.

The Global Stranding Network (GSN) supports international marine mammal stranding response. The GSN assists with strandings of all marine mammal species and works closely with the International Whaling Commission’s Strandings Initiative to share best practices, provide relevant trainings, and increase collaboration and capacity to respond to marine mammal strandings worldwide.

Unusual Mortality Events (UMEs)

When more than two marine mammals strand at the same time in the same general area it is known as a mass stranding. Mass strandings occur quite frequently in the United States and in Cape Cod, Massachusetts in particular. These strandings involve anywhere from a few, to several hundred animals. Unusual Mortality Events (UMEs) are specifically defined under Title IV of the MMPA as strandings that are “unexpected, involve a significant die-off of any marine mammal population, and demand immediate response,” including scientific investigation.

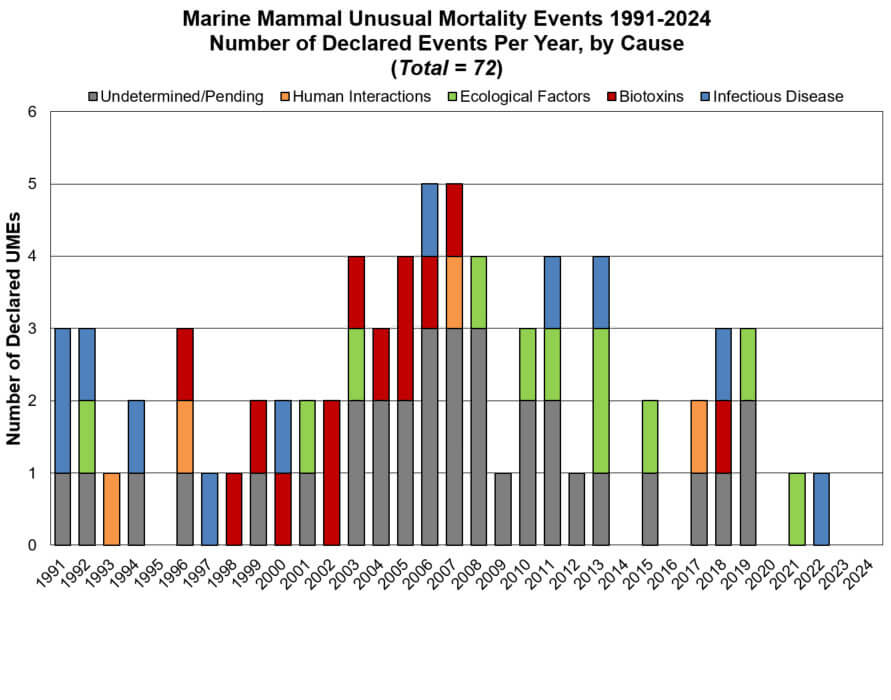

Since the UME program was established in 1991, there have been more than 72 formally declared UMEs across all coasts of the United States. The most commonly affected species are bottlenose dolphins, California sea lions, and Florida manatees and the most common UME causes include infections, human interactions, and biotoxins (poisonous substances produced by living organisms, usually Harmful Algal Blooms, HABs). For more information on UMEs, visit NOAA’s UME Web page.

UMEs between 1991 and 2024, showing the number of declared events and known causes per year. (NOAA)

Biosurveillance and Baseline Health Research

A bottlenose dolphin in Barataria Bay, LA receives a cardiac ultrasound (National Marine Mammal Foundation).

Biosurveillance and baseline health research are also important components of the MMHSRP. Targeted studies of live marine mammals, including capture-release health assessments, visual assessments, photogrammetry, and remote tissue sampling, are used to monitor the health of populations. These health data have been used to assess population trends (Schwacke et al. 2024) and to help to interpret information from UME investigations.

Marine Mammal Health Monitoring and Analysis Platform (Marine Mammal Health MAP)

The Commission recognizes the importance of understanding the health of marine mammals as part of healthy ecosystems, and we are committed to supporting a national plan for temporally- and spatially-structured health surveillance, and the development of the Marine Mammal Health Monitoring and Analysis Platform (Marine Mammal HealthMAP).

Stranded juvenile California sea lions recuperating at The Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito. (The Marine Mammal Center)

In December 2022, Congress enacted the James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act, which include the Marine Mammal Research and Response Act (MMRA; pg. 1587). The MMRA instructs NOAA to establish HealthMAP, and to make it publicly accessible through a web portal. The Act also requires that additional data collected from stranding or entanglement events, such as weather and tide conditions, morphometrics, histopathology, toxicology, microbiology, virology, parasitology, and life history data, be collected by NOAA, as available from the stranding network members. These additional data will support modeling and analyses that will improve our understanding of the causes of strandings, and help to identify emerging threats.