Manatees and Warm-Water Refuges

To change the status of Florida manatees under the Endangered Species Act, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) must assess the severity of existing and foreseeable threats to their survival. Virtually all Florida manatees, including those in southernmost Florida, require small localized warm-water refuges to survive the coldest winter weather (Laist and Reynolds 2005a). Currently, two-thirds of all manatees rely on power plant outfalls to survive the coldest winter days (Laist et al. 2013). The projected operational lives of power plants currently used by manatees do not extend beyond 35 to 40 years (Laist and Reynolds 2005b). As power plants are retired, it is unclear whether natural warm-water refuges—principally warm-water springs in the central and northern parts of the state and passive thermal basins in the southern part of the state—will be sufficient to support current numbers of animals.

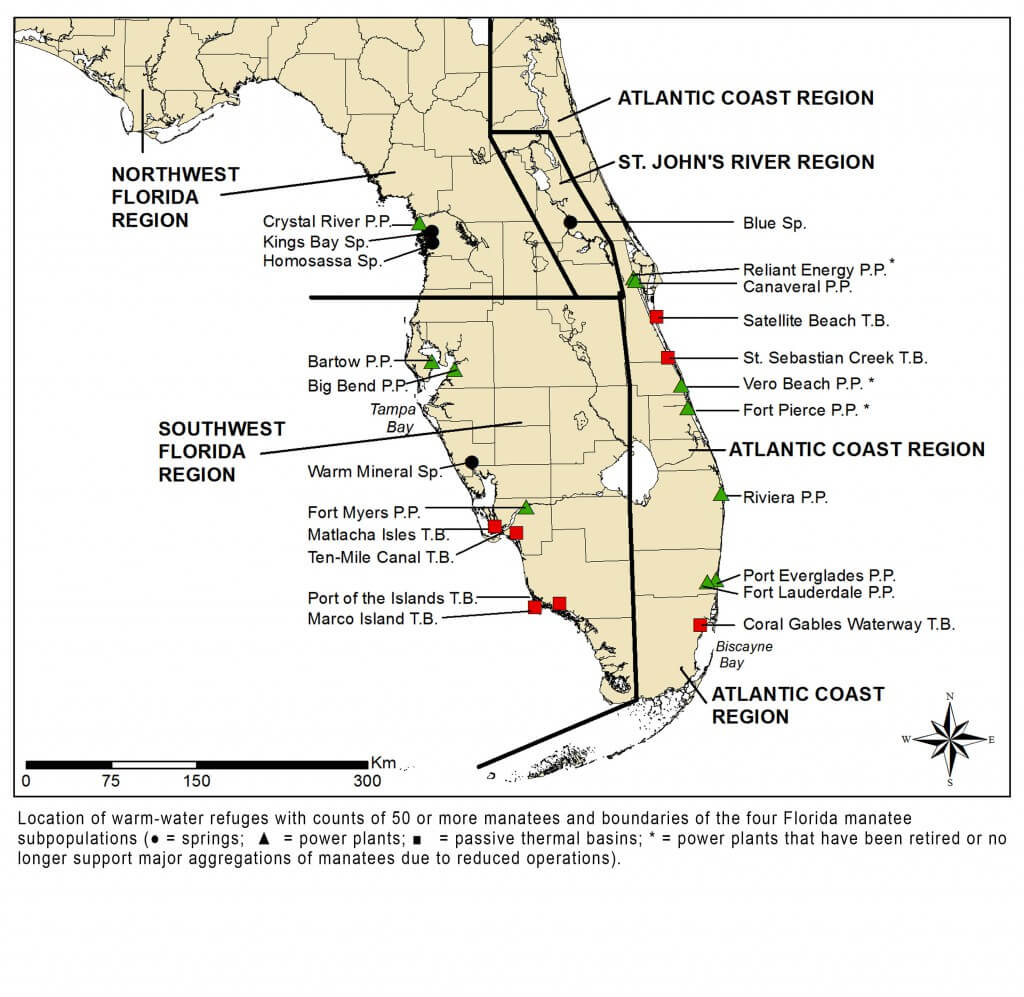

Locations of warm-water refuges with counts of 50 or more manatees and boundaries of the four Florida manatee subpopulations. (Mina Innes)

Warm-water springs are believed to be the best natural winter habitats for manatees and most have either been blocked by dams or other structures, altered by construction, degraded by overuse, used intensively for recreation, or are subject to declining spring flow due to groundwater pumping for human consumption or agricultural use. About 18 percent of all manatees now use warm-water springs (principally Blue Spring on the St. John’s River and Kings Bay at the head of the Crystal River) to survive cold weather. Increasing the proportion of manatees dependent on springs will require decades of work to improve access and conditions at springs and needs to be done before power plants are closed.

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission (FWC) and the FWS have begun efforts to improve access and protection of natural springs, many of which are currently underutilized by manatees. Major accomplishments in this regard include the following:

- The spring run at Fanning Spring on the Suwannee River has been dredged to improve manatee access.

- Sea grass has been replanted in the Wikiwatchee Spring to provide a food source for overwintering manatees.

- The Chassahowitzka Spring run has been dredged to improve manatee access.

- Plans are being developed to dredge the spring run for Warm Mineral Spring.

- Lands around Three Sister Spring off Kings Bay have been purchased to prevent its development and are now being managed as part of the Crystal River National Wildlife Refuge.

- A rock weir in the spring run at Three Sisters Spring has been removed and a no-entry manatee sanctuary area has been established near the mouth of the spring run to limit harassment by recreational divers.

- A new basin and spring run at Ulele Spring off Tampa Bay has been restored to allow manatee access.

- Minimum flows for spring discharges have been established for several springs including Blue Spring, Homosassa Spring, Wikiwatchee Spring and Chassahowitzka Spring and will be established for additional springs used by manatees as possible.

- In 2015 the Army Corps of Engineers constructed a new thermal refuge for manatees along the Faka Union Canal in southwest Florida. Its purpose is to replace a thermal basin expected to be lost due to a Florida Everglades restoration project at Port of the Islands. The new refuge consists of a series of three 20 ft deep basins on a 10 acre dredge spoil deposit along the canal that tapped a warm shallow saltwater aquifer that will maintain an elevated water temperature throughout the winter.

In addition, the FWC and FWS are taking steps to complete a warm-water refuge management plan identifying actions that should be taken to ensure that Florida manatees have adequate warm-water refuges when power plants creating outfalls now used by manatees are eventually retired and closed. When that plan is completed, Florida Power & Light Company, which operates plants used by the large number of manatees, plans to convene a workshop to assess actions that will be needed to prepare for eventual power plant closures.

Recognizing that it has taken 50 years to develop the current dependency of manatees on power plants, it could take a comparable period of time to carry out research, implement measures to improve alternative refuges not dependent on power plants, and provide time for manatees to increase their use of those sites. In several Commission letters (21 April 2008, 26 April 2010 and 21 September 2011) to the FWS, we provided extensive comments and recommendations on this issue. Among other things, our letters recommended that FWS (1) reconvene a warm-water task force disbanded in 2007, (2) hold regional meetings to identify long-term warm-water networks and related research and management actions for each of the four Florida manatee subpopulations, and (3) work with Florida utilities whose power plants attract manatees during winter months to establish a fund that would support actions necessary to assure alternative warm-water refuges are available before power plants are retired (See also the Florida manatee sections of the Marine Mammal Commission’s Annual Reports from 2003 to 2012). As noted under the discussion of the listing status for West Indian Manatees, in the FWS’s April 2017 decision to reclassify West Indian manatees as threatened, the agency announced that it plans to reconvene the warm-water task force. FWS also recommended to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection to include a condition in its periodic renewals of NPDES permits authorizing thermal discharge from power plants used by manatees that would require those utilities to provide funding mechanisms to cover costs associated with transitioning manatees from reliance on power plants to use of suitable non-industry dependent warm-water refuges.