Vaquita

The tiny vaquita porpoise is the world’s most endangered marine mammal. Its numbers are decreasing with approximately 10 remaining. Vaquitas die from entanglement in illegal gillnets. Gillnets are used in a lucrative illegal fishery for totoaba that serves an illegal trade of swim bladders to China as well as in shrimp and finfish fisheries. Although their use has been banned in all fisheries, and in the absence of government enforcement or support for the use of alternative gear, gillnets continue to be used in all of these fisheries, including in the Zero Tolerance Area designated for protection of the vaquita in their habitat.

Surfacing vaquitas. (Paula Olson)

Species Status

Abundance and Trends

The tiny vaquita porpoise is the world’s smallest and most endangered cetacean species. The vaquita remains on the brink of extinction with approximately 10 remaining in 2023. Analysis of acoustic data from 2011 to 2018 combined with visual observations in 2017 and 2018 showed an estimated average annual rate of decline of 33%, corresponding to a population decline of 98.6% over this period. Eleven dead vaquitas were found between March 2016 and March 2020 and the cause of death for eight of those animals was directly attributed to gillnets.

Distribution

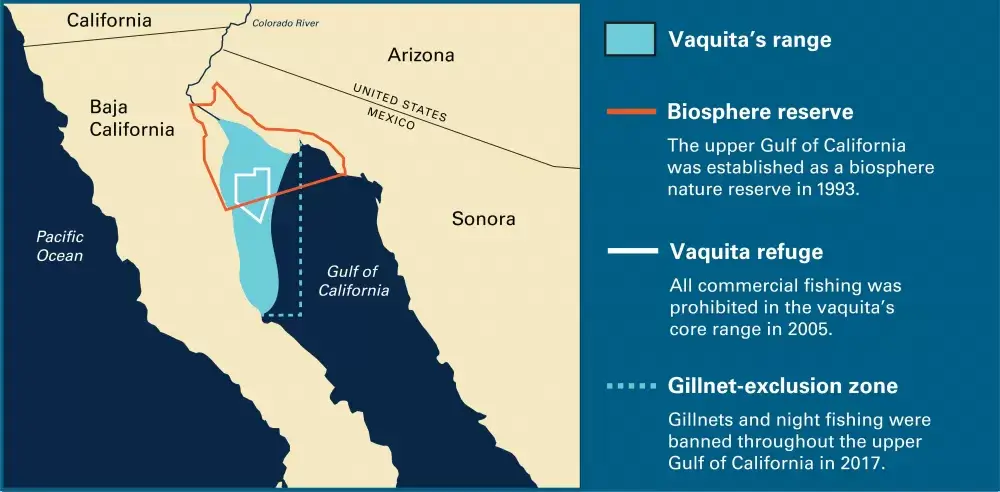

The vaquita split from its closest taxonomic relatives 4.8 million years ago and is now endemic to a small range (4,000 km2) in the turbid waters of the northern Gulf of California, Mexico.

Vaquita range map and protection zones. Photo credit: Smithsonian Institution

VaquitaCPR

Given the extreme concern over the safety of vaquitas in their natural habitat, the eighth meeting of theComité Internacional para la Recuperación de la Vaquita (CIRVA-8), held in November 2016, recommended that the Mexican Government institute a carefully planned, step-wise attempt to determine whether some vaquitas could be caught and held in a temporary sanctuary until they could be safely returned to a gillnet-free environment. CIRVA-9 concluded that given the recent deaths of at least six animals since CIRVA-8 and the high levels of illegal fishing activity in the Upper Gulf, the only hope for the survival of the species in the short term was to capture vaquitas and bring them into human care. Therefore, CIRVA strongly endorsed the Vaquita Conservation, Protection and Recovery (VaquitaCPR) plan and recommended that as many individuals as possible be captured in October and November 2017 and held until the Upper Gulf is safe for their return. There was grave concern that the vaquita will follow the Yangtze River dolphin (baiji) and become the second cetacean species brought to extinction in the 21st century if further action is not taken to save the species.

VaquitaCPR undertook an ambitious field season, based out of San Felipe, Mexico from 10 October to 10 November 2017. A team of 65 scientists from nine countries was on the water for five full days and eight partial days during the operational time frame as dictated by weather. Vaquitas, in groups of one to three, were seen on eight of these days. Catch nets were set on three days and two vaquitas were captured during field operations. As noted on the VaquitaCPR website, “The first animal, an immature female, was released after veterinarians determined she was not adapting to human care. The second animal, a mature female, that wasn’t pregnant or lactating, was released after not being able to adapt to human care at “El Nido.” During the second release emergency medical care was required. Despite heroic efforts by the veterinary team to save the animal’s life, she did not survive.”

Following the field season, the Mexican government, VaquitaCPR, and CIRVA evaluated next steps. In early December 2017, CIRVA conducted its 10th meeting at the Southwest Fisheries Science Center in La Jolla, California and released the CIRVA-10 report. Their main conclusion was that the status of the vaquita continues to worsen and that no more than 30 animals remained by mid-2017. Further, the committee accepted the conclusions of the VaquitaCPR team and an independent review panel that additional rescue efforts should be suspended. Moving forward, CIRVA recommended to the Government of Mexico that the first and immediate conservation priority must be to strengthen enforcement efforts and fishing regulations, including a complete ban on gillnet possession and use throughout the range of the vaquita. The CIRVA team also issued a specific recommendation to implement ‘enhanced’ enforcement during the December 2017 – May 2018 totoaba season in areas of vaquita and totoaba gillnet overlap.

One of the real advances of this effort was the use of underwater acoustic monitoring to detect vaquitas on a daily basis and provide information for the visual search team. This was built on the annual program of acoustic monitoring that has informed estimation of vaquita abundance over the last decade. Despite the extensive loss of equipment stolen by fishermen, real-time acoustic monitoring has been used to a limited extent to inform visual sighting efforts in 2020 and 2021.

What the Commission Is Doing

The Marine Mammal Commission supports U.S. government efforts with the Government of Mexico and the international community to address the threat to this critically endangered marine mammal – incidental mortality in illegal and legal fisheries bycatch – and it has a long history of providing funding and international scientific and technical expertise to aid those efforts. The Commission has supported the meetings of the international recovery team (CIRVA) and international efforts to assess vaquita abundance, trends, and the effectiveness of measures taken by Mexico to slow the species’ decline. The Commission has supported annual acoustic monitoring of this species since 2011 and it is committed to continuing to assist Mexico in its efforts to prevent the vaquita’s extinction. Members of Commission staff, Commissioners, and Scientific Advisors served as advisors to the VaquitaCPR program, were on the leadership team, and participated in all aspects of planning and fieldwork.

Over the past decades, the Commission has taken a leadership role, in collaboration with other U.S. government and Mexican agencies, to explore ways to provide communities in the northern Gulf of California with financially, socially, and ecologically viable alternatives to the gillnet fishing that is currently driving the vaquita toward extinction and to build markets for seafood caught without harming vaquitas. The Commission has provided financial support to develop, test, and introduce vaquita-safe fishing gear and methods, increase the effectiveness of protected areas, strengthen fisheries enforcement and trade controls, and develop market incentives to sell products caught with vaquita-safe gear. The Commission will continue to press for enforcement of the permanent ban on gillnets whether used by fishermen in the cartel-driven totoaba fishery or the fishery for shrimp and finfish.

Commission Reports and Publications

Related reports:

June 2023: Survey report for vaquita research 2023

December 2021: Survey report for Vaquita research 2021 final.docx (iucn-csg.org)

April 2021: Report on using expert elicitation FINAL.docx (iucn-csg.org)

Commission Letters

| Letter Date | Letter Description |

|---|---|

| September 21, 2017 | |

| April 10, 2009 |

Learn More

Threats

Vaquitas are threatened by entanglement in gillnets used to illegally catch the endangered totoaba (Totoaba macdonaldi), a large and endangered fish species also endemic to the upper Gulf of California. This fishery, which first re-emerged in the early 2010’s and involves large-mesh gillnets exceptionally lethal for vaquitas, is driven by the high price and demand for totoaba swim bladders in China. Use of gillnets for shrimp and finfish fisheries, which also entangle vaquitas, has been banned in the upper Gulf of California since 2015.

Both active and abandoned gillnets pose a threat. In May 2016, CIRVA-7 noted that many totoaba nets were being abandoned as poachers sought to avoid detection and enforcement, and the committee called for efforts to find and remove such gear in the range of the vaquita. In response Sea Shepherd Conservation Society initiated efforts to remove and destroy or recycle the illegal gillnetting gear. This program, which was joined by the Museo de la Ballena and the Government of Mexico, continued through 2020 as the illegal totoaba fishing continued unchecked, with 106 recently set nets removed by the end of February in the 2019-20 fishing season by Sea Shepherd vessels alone. The net removal program was halted in January 2021 following extensive civil unrest in late 2020.

In fall 2019, the Mexican government announced it would no longer provide compensation to the fishermen whose livelihoods were threatened by the prohibition of gillnet fishing for shrimp and finfish within the upper Gulf. The government also refused to provide support for fishermen wishing to use alternative gear that would not entangle vaquitas. Facing economic hardship, many of the displaced fishermen returned to fishing for shrimp with gillnets without authorization.

The deployment, by the Mexican Navy, in August 2022, of 193 concrete blocks with 3m high metal hooks designed to entangle gillnets in the Zero Tolerance Area (ZTA) significantly reduced the fishing effort in the major portion of the current range of the vaquita.

Although the main threat to vaquitas is entanglement in gillnets, there is some concern that their small population size may also affect their persistence. The collaborators in the Vertebrate Genomes Project, including The Rockefeller University, Southwest Fisheries Science Center-NOAA, and the Mexican National Commission on Natural Protected Areas (CONANP) sequenced the vaquita genome from living tissue salvaged from animals caught in VaquitaCPR project. Analyses suggest that low genome-wide heterozygosity is due to long-term persistence as a small population rather than a recent loss of diversity, for example, from inbreeding, that might accelerate extinction. This suggests that vaquitas may be able to maintain diversity necessary for population health despite their small population size. These results support the findings of a 2022 study that suggest that vaquitas are not “doomed to extinction by inbreeding depression” and that they could recover if entanglements ceased.

Current Conservation Efforts

On 24 September 2020 the Government of Mexico announced an agreement between the Ministries of Agriculture and Rural Development, Environment and Natural Resources to promote the sustainable use of marine resources and the protection of the vaquita. The agreement established measures to regulate fisheries and landing sites in the northern Gulf of California and required the installation of vessel monitoring systems on all vessels with a permit or concession. The agreement also established a 225 square kilometer ZTA to serve as a year-round refuge area for protection of vaquita.

The 2022-2023 fishing season saw a 90% decrease in gillnetting in the ZTA. This is attributed to the deployment by the Mexican Navy, in August 2022, of 193 concrete blocks with 3m high metal hooks designed to entangle gillnets. The Navy and Sea Shepherd Conservation Society are monitoring the presence of fishing activity and taking action to relocate fishing vessels outside the ZTA and remove gillnets.

Despite these efforts, there is continued concern in the international scientific community that the Government of Mexico continues to question the incontrovertible evidence that gillnets are the primary source of vaquita mortality, and international environmental groups continue to call for further action to save the vaquita from extinction.

On 26 July 2018, as rampant totoaba fishing continued, the U.S. Court of International Trade issued a preliminary injunction in a suit brought by conservation organizations “requiring defendants — several United States agencies and officials, and here collectively referred to as “the Government” — to ban the importation of fish or fish products from any Mexican commercial fishery that uses gillnets within the vaquita’s range.” On March 4, 2020, the National Marine Fisheries Service revoked the comparability finding under the MMPA for a number of fisheries operating in the habitat of the vaquita. The MMPA requires prohibition of the import of seafood caught with commercial fishing technology which results in the incidental kill or incidental serious injury of ocean mammals in excess of United States standards.

In June 2017, the Government of Mexico announced a permanent ban on the use of gillnets in the shrimp and finfish fisheries of the Upper Gulf of California to replace the two-year gillnet ban. An initiative between the “Museo de la Ballena” and local fishing cooperatives to develop alternative fishing gear for shrimp was launched in 2019. Three different types of “suripera” nets were designed by the local fishermen, who started testing them in late October 2019. The fishing gear appears to work effectively when shrimp are in shallow water, but is less effective in deeper water. Tests are continuing with the goal of refining the designs for broader testing.

The VaquitaCPR program (see Species Status section) began in 2017. The program was a carefully planned, step-wise attempt to determine whether some vaquitas could be caught and held in a temporary sanctuary until they could be safely returned to a gillnet-free environment. Unfortunately, vaquitas did not adapt well to captivity and capture attempts were discontinued. Instead, the team launched Project Esperanza, which focuses on gillnet removal, acoustic monitoring, supporting local fishers and organizations, and raising global awareness of the plight of the vaquita.

On April 16, 2015, the President of Mexico announced new measures to protect vaquitas, which have been largely implemented by the Mexican Navy and other agencies in a strong show of commitment. These included expansion of the protected area for vaquitas to encompass their entire range, a two-year ban on gillnets within this area, concerted enforcement, support for alternative fishing methods, and compensation to the fishing communities affected by the ban.