Barataria Bay Bottlenose Dolphins

The Barataria Bay Estuarine System population of common bottlenose dolphins resides year-round in Barataria Bay, a large estuary in southern Louisiana. This population of bottlenose dolphins is genetically differentiated from other nearby bottlenose dolphin populations. Scientists estimate that the Barataria Bay dolphin population has declined by about 45 percent due to effects of exposure to oil from the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Projections show the population is now threatened with extinction from operation of the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion Project, which will divert large amounts of fresh water into Barataria Bay.

Bottlenose dolphins form strong but fluid social bonds. Photo credit: NOAA

Species Status

Abundance and Trends

Barataria Bay is a shallow estuary in southern Louisiana, approximately 110 km long and 50 km wide. The southern portion of the bay is connected to the Gulf of America (formerly the Gulf of Mexico) by channels, or ‘passes’. The Barataria Bay population (stock) of bottlenose dolphins is genetically distinct from other dolphin populations occurring in Gulf coastal waters, including other bay, sound, and estuary (BSE) dolphin populations. Among the 31 BSE bottlenose dolphin populations in the northern Gulf, the Barataria Bay population is one of the largest with around 2,000 dolphins.

Oiled dolphin in Barataria Bay, Louisiana. Photo credit: Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries

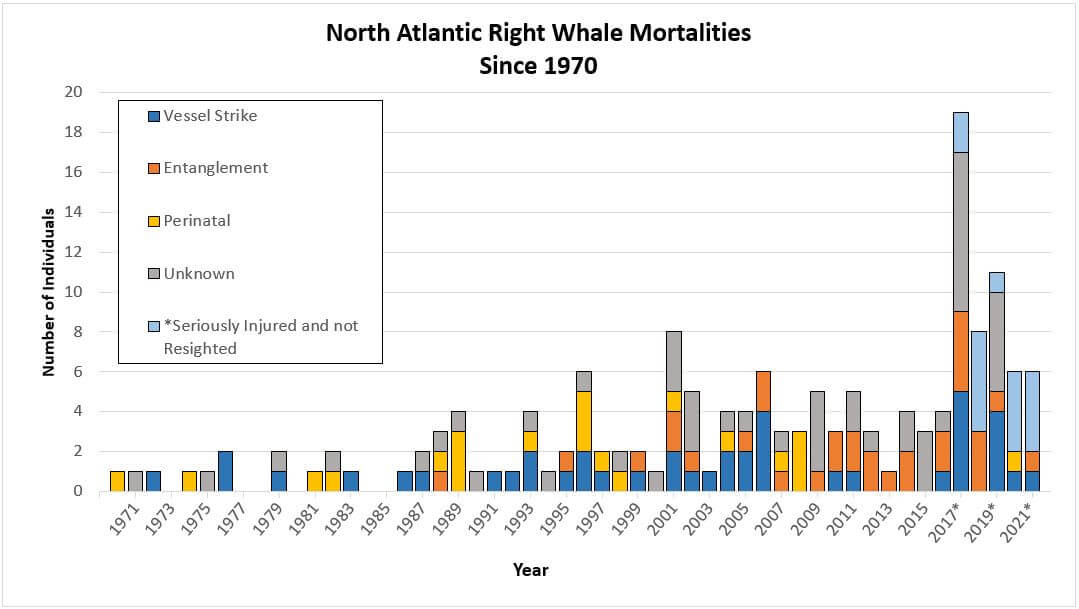

The Barataria Bay dolphin population was heavily impacted by the 2010 Deepwater Horizon (DWH) oil spill, which released an estimated 168 million gallons of oil into the Gulf over 87 days. The oil contaminated surface waters and nearshore habitats hundreds of miles away from the wellhead, including Barataria Bay.

At the time of the DWH spill, the abundance of Barataria Bay dolphins was unknown. However, analysis of data from photographic surveys done shortly after the spill indicated that there were over 3,000 dolphins in Barataria Bay at that time. Following the spill, many dolphins in Barataria Bay died, and many of those that survived could not successfully reproduce. Many of the dolphins that survived also had lung disease, impaired stress response, and other chronic diseases. A population dynamics model predicted that, due to disease and failed reproduction, the Barataria Bay population would continue to decline for 10 years after the spill, dipping to a low point less than half of its pre-spill abundance before beginning a slow recovery. Analysis of subsequent photographic survey data suggests that the abundance of the Barataria Bay dolphin population was around 2,000 dolphins in 2019.

Threats to the Population

Ongoing threats to Barataria Bay dolphins include chronic disease and reproductive failure in dolphins that were exposed to oil from the DWH spill, and interactions with commercial and recreational fisheries. However, the greatest threat to the Barataria Bay dolphin population comes from building and operating the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion (MBSD) project in Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana. The MBSD project will divert water and sediment from the Mississippi River into the northern portion of Barataria Bay. The goal of the project is to rebuild marshland that has been eroding for decades due to oil and gas extraction, canal excavations, extreme weather events, subsidence, and sea level rise. However, operation of the MBSD will also significantly alter the dolphins’ estuarine habitat by adding large amounts of freshwater into the bay and thereby lowering its salinity.

Scientists modeled the habitat changes expected to happen with the MBSD project to determine the likely impacts to the Barataria Bay dolphin population. They predict a catastrophic decline in the Barataria Bay dolphin population, with over 500 dolphins (one quarter of the population) dying within the first year of the MBSD operation. Dolphins that reside in the central and western portions of the bay are expected to be “functionally extinct” after just 10 years of the MBSD’s operation. After 50 years of operation, bottlenose dolphins across the entire bay will be almost entirely gone, with only a small number remaining near the bay’s barrier islands.

The Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) generally prohibits taking marine mammals, absent authorization. It was doubtful that the project would meet the requirements to secure an authorization under the MMPA’s existing provisions, so, Congress passed legislation directing the Secretary of Commerce to waive the MMPA’s taking prohibition in spite of the predicted consequences of the MBSD project for the Barataria Bay dolphin population. Additional information about the MMPA waiver can be found on the “More” tab.

A Dolphin Intervention Plan was included in the Final Environmental Impact Statement as part of the MBSD project’s monitoring and adaptive management plan. However, the activities outlined in the plan are not focused on mitigation measures to avoid the project’s adverse impacts on the Barataria Bay dolphin population. Instead, they are focused on documenting and responding to dolphins that are injured, become ill, or are killed by the environmental changes in Barataria Bay that result from the MBSD project.

Given the large number of dolphins that will be exposed to extremely low salinity for prolonged periods of time, intervention (i.e., rescue and rehabilitation or relocation) will not be practical for more than a few animals. There is limited capacity to care for sick and distressed dolphins at marine mammal rehabilitation facilities in the northern Gulf. Even if some dolphins are rescued and rehabilitated, the changes to their habitat would preclude successful reintroduction, forcing them to either remain in captivity or be relocated to another area, assuming another area with suitable habitat could be found. Rescue and rehabilitation efforts could save a small number of individual dolphins, but will not prevent the population from declining towards extinction.

What the Commission Is Doing

When the Louisiana Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion (MBSD) project was first proposed as a Deepwater Horizon oil spill restoration activity in 2015, the Marine Mammal Commission identified threats to the Barataria Bay dolphin population posed by the project. The Commission has since recommended several alternatives and additional measures that could be taken to reduce impacts on dolphins while arguably allowing the project to meet its objectives.

The Commission provided detailed comments on its concerns and suggested alternative approaches to entities responsible for planning, reviewing, and approving the MBSD project, including the Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, the Louisiana Deepwater Horizon Trustee Implementation Group, NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and the RESTORE Act Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Council. Despite the Commission’s recommendations, the project was approved without the inclusion of additional measures to reduce adverse impacts on dolphins. Construction of the project began in August 2023.

The Commission convened a webinar in March 2021 to provide information on the potential impacts of low-salinity exposure on dolphins and their prey, review the findings of the 2019 northern Gulf bottlenose dolphin Unusual Mortality Event, identify data needs, and discuss options for mitigating and monitoring impacts to dolphins and their prey from future low-salinity exposure. For more information and to view the webinar, see ‘Effects of Low-Salinity Exposure on Bottlenose Dolphins.’

The Commission continues to remain an active participant in identifying strategies for monitoring and mitigating harm to the Barataria Bay stock of bottlenose dolphins from the MBSD project. A strategy for monitoring bottlenose dolphins’ response to freshwater prior to and during MBSD operations is currently under development by NMFS. The Commission and others provided input to NMFS on monitoring priorities at a workshop held in December 2023. In August 2024, the Commission provided additional input at a workshop on possible intervention strategies, emphasizing testing that might be conducted during the construction phase of the project. Strategies found to be successful, such as deterring dolphins away from freshwater flows or translocating dolphins to less affected areas, along with other data collected during the construction phase, could lead to changes in how the MBSD operates so as to avoid or minimize harm to individual bottlenose dolphins.

Commission Reports and Publications

For more information on the effects of low salinity water on bottlenose dolphin health and survival, please refer to the Commission’s March 2021 webinar on “Effects of Low-Salinity Exposure on Bottlenose Dolphins.”

Commission Letters

| Letter Date | Letter Description |

|---|---|

| October 18, 2022 | |

| June 2, 2021 | |

| April 20, 2020 | |

| March 12, 2018 | |

| February 5, 2018 | |

| October 7, 2016 | |

| December 4, 2015 | |

| September 28, 2015 |

Learn More

Marine Mammal Take Authorization

The Marine Mammal Protect Act (MMPA) generally prohibits taking of marine mammals, that is “to harass, hunt, capture or kill, or attempt to harass, hunt, capture, or kill” them, absent authorization. The Act includes a variety of ways for securing such authorization to “take” marine mammals. One common way of securing authorization is through issuance of an incidental take authorization (under section 101(a)(5)) that authorizes the taking of small numbers of marine mammals incidental to an otherwise lawful activity. However, this type of authorization requires a finding that the taking will have no more than a negligible impact on the affected species and stocks, a finding that could not be made for the Barataria Bay dolphin population as the project was proposed.

Another type of generally available authorization is a waiver of the MMPA’s moratorium on taking marine mammals. A key finding for obtaining a waiver is that the taking will not disadvantage any species or stock (i.e., population) of marine mammals. Such a finding could not be made for the Barataria Bay dolphins, given the projected impacts of the freshwater diversion on the population. Hence, a waiver would not normally be available for the project. However, Congress passed legislation in 2018 {Section 20201 of Public Law 115-123, the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018) directing the Secretary of Commerce to issue a waiver under the MMPA notwithstanding the otherwise applicable requirements. The waiver applies to three Louisiana wetland restoration projects-the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion, the Mid-Breton Sound Sediment Diversion, and the Calcasieu Ship Channel Salinity Control Measures project. The waiver required only that the State of Louisiana, in consultation with the Secretary, “upon issuance of [the] waiver,” take steps to:

- to the extent practicable and consistent with the purposes of the projects, minimize impacts on marine mammal species and population stocks; and

- monitor and evaluate the impacts of the projects on such species and population stocks.

In essence, Congress determined that completing these projects took precedence over the anticipated detrimental effects on dolphins. Louisiana is required to take steps to minimize these impacts, but only if doing so would be practicable to implement and would not undermine achieving the purposes of the project. The state of Louisiana and the Secretary of Commerce are responsible for determining whether mitigation measures are practicable, and whether such measures would undermine achieving the purposes of the project.

Research and Monitoring

Following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, a number of studies were conducted to understand and quantify the effects on the bottlenose dolphins in Barataria Bay, as well as other dolphin and cetacean populations throughout the northern Gulf of Mexico. These studies, part of the Natural Resource Damage Assessment (NRDA) led by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration with other co-trustees, included necropsies of dead stranded dolphins, capture-release health assessments of live dolphins, and photographic surveys to determine dolphin abundance, reproductive success, and survival rate. Collectively, the findings from the studies demonstrated that the Deepwater Horizon oil spill substantially impacted the health of Barataria Bay dolphins, leading to reproductive failure and increased mortality. Findings from the NRDA studies were summarized in the Deepwater Horizon Trustees’ Final Programmatic Damage Assessment and Restoration Plan. In addition, many of the studies were compiled and published in a Special Issue of the scientific journal Endangered Species Research: Effects of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill on protected marine species (Volume 33, 2018).

A group of dolphins swim in Barataria Bay. Photo credit: National Marine Mammal Foundation

The Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) provided funding for continued studies of Barataria Bay dolphins that were exposed to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. The GoMRI studies documented the persistence of chronic disease such as lung disease and impaired stress response. A model developed by the GoMRI researchers estimated that in the ten years following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, the Barataria Bay dolphin population had declined by 45 percent.